Tags

Baus, crosswords, fame, Nixon, political strategy, restaurant critic, wine

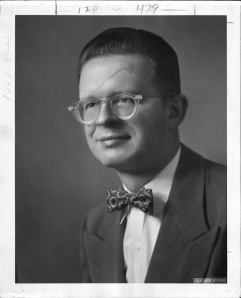

How do we measure success? One generally accepted yardstick is fame. We generally think of people who are well-known, either to the general public or within a smaller professional or topical sphere, as successful. Take, for example, Herbert M. Baus, who achieved some modest measure of recognition during his lifetime. He was a pioneer among political consultants, starting a firm in California in the late 1940s with his partner, William Ross, and for 20 years participating in a number of successful initiatives and campaigns. He helped get Daylight Saving Time established in California, and he ran successful campaigns for candidates ranging from Pat Brown, Sr., to Richard Nixon. (He would also later be one of the first of Nixon’s old allies to publicly urge him to resign from the presidency.) Baus and Ross co-wrote a book on campaign strategy called “Politics Battle Plan” in 1968, around the time that Baus retired from the consulting firm at age 54. He spent much of the rest of his life working hard on things he genuinely enjoyed. A gastronome, he became a newspaper restaurant critic and also published a book on wines.

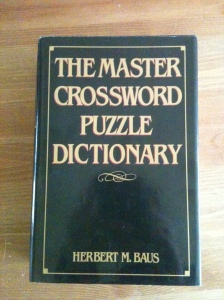

Baus was also a crossword enthusiast, one who was dissatisfied with the reference materials available at that time. Ordinary dictionaries, after all, were often too straightforward to be of much help; crossword clues tended to be oblique or allusive. Plus, Merriam-Webster might be able to tell you that Ibsen was a Norwegian playwright, but wouldn’t work in reverse; there was no way to look up “Norwegian”, “playwright”, or “Norwegian playwright” and find “Ibsen”. So Baus decided to write a special dictionary just for crosswords. He spent a few years gathering and indexing clues from various sources, and came out with The Expert’s Crossword Puzzle Dictionary in 1973. It was new, and useful, but Baus very quickly came to feel it was incomplete. “I thought if it was worth doing, it was worth overdoing,” he said, and so he spent several more years adding to the project. The result was the 1,693-page book Master Crossword Puzzle Dictionary, which came out in 1981. It provided more than one million possible answers to crossword clues.

In 1997, I stumbled across the web site for The National Puzzlers’ League, the oldest organization in the world dedicated to writing and solving word puzzles. As a lover of puzzles and word games since childhood, I was immediately captivated. I soon became totally engaged with this new group of like-minded comrades, and eagerly adapted to their challenging and sometimes obscure puzzle constructions. I also learned about a whole bunch of solving resources I had never even heard of before – Brewer’s Dictionary of Phrase and Fable, for example, or a printed compilation of words in alphabetical order by last letters (so you could solve puzzles when all you had was _ _ _ _ U Z). Bear in mind that the Internet was still pretty young; nowadays a lot of tools like anagram solvers and Wikipedia are free online, but even in the late ‘90s books were the best source of this kind of help. And the book that NPL members held in highest regard was the Master Crossword Puzzle Dictionary. It was so well-constructed and so comprehensive that it was always most likely to provide the clue that would help crack a really tough puzzle. And even though it was out of print and difficult to find, most NPL members had tracked down a copy, so it was common for members describing their solving experiences to write, “. . . so then I Baused the last word and that led to . . .”. Yes, it was so heavily relied upon that, rather than write out “looked it up in the Master Crossword Puzzle Dictionary,” folks just used Mr. Baus’s name as a verb.

I was fascinated, and I asked some of my new puzzling acquaintances: Who was this Herbert M. Baus? Had he belonged to the NPL? Did anyone know him? It turned out that none of us did. He was just the guy who wrote the most useful crossword dictionary ever.

Well, even though the Internet was still young, it was still the Internet, so I got online and did some research. Eventually I found enough information about Mr. Baus’s work as a restaurant critic in Southern California to realize, first, that if he was still alive, he had to be in his eighties, and second, that I had found a telephone number that seemed pretty likely to belong to him. I don’t like making telephone calls to strangers. But it seemed improper to me that he apparently had no idea that this small (at the time the NPL had a little more than 400 members) but very intense clique of puzzlers was using his name as a verb. That was the kind of fame that memorialized people like Franz Mesmer and Louis Pasteur. Surely Mr. Baus would want to know about that! So I took a deep breath and called.

Mrs. Baus answered the phone, and I rather hurriedly explained that I was looking for the author of the Master Crossword Puzzle Dictionary to let him know how some kindred spirits were using his book, and so if this was indeed the home of that Herbert M. Baus, I would love to talk to him. She told me that I had the right person, but that he was not in the best shape for telephone conversations and it might be difficult for me to understand him. He had Parkinson’s disease. I said that I would be happy to speak with him if he felt up to it.

He came on the line, and I introduced myself, and explained about the NPL, and how much we loved puzzles and relied upon his book. So much so that his name had entered our common vocabulary, I explained, trying to impress upon him what I saw as the significance of the minor immortality. The tone of his responses sounded positive to me, but I could not make out any of the content; his Parkinson’s had clearly progressed quite far. His wife, however and of course, could interpret his words, and when she got back on the phone she assured me that he had understood what I had told him. She said that he had been trying to tell me that he was very pleased to have learned that puzzle people were finding his book so useful. She did not indicate that he had said anything about becoming a verb.

Several months later, Mr. Baus died, which I learned about sometime after the fact. I stumbled across his obituaries on the Internet, and it was then that I discovered that he had once worked as a journalist and as a political consultant and had helped start Richard Nixon on his path to the White House. He was somebody who had experienced a narrow beam of the limelight, who knew what it was like to be recognized by strangers. But the thing of value that he had taken from our telephone conversation — the reason I am so glad I made that phone call — was not the fact that his name would live on, at least among a circle of simpatico fanatics. It was the fact that those fellow wordplay devotees found value in his marvelous creation. The verbing of his name was just the needle on the value-o-meter.

Fame can be a measure of success. But it is not success itself. Real success might just be defined as doing something of value to yourself that turns out to be of value to others.

Love, love this blog. Thanks for writing it!

Seems like no matter what topic you choose to write about, you never fail to entertain and/or inform. When you choose an entertaining and informative topic, that’s just gravy!

what a privilege for both you and the infamous Mr. B– a heartfelt story-thanks for sharing,– Buttorkup aka scrbblewhz

What a wonderful article! Story telling is the most effective way of conveying information to people and you did it very effectively.