Tags

advice, authority, counsel, detour, Huntington Beach, Orange County, Pacific Coast Highway, Santa Ana

So much of Southern California is not what it purports to be. Maybe this is why the film industry ended up here. For some people, it might be where their career advisors belong.

Last weekend I was getting some exercise on the Santa Ana “River” Trail. This is a pair of pedestrian and bicycle paths that run alongside the banks of the Santa Ana “River”, in quotes because it is really more of a theoretical river than an actual one. In real life, I think if you can leap over a course of water without getting your sneakers wet, it is considered a “rivulet” or a “rill” or maybe just a “mobile puddle”. Closer to its outlet in Huntington Beach, the water broadens, but that could just be backwash from the Pacific or, more likely, “river” water that just collected there because it couldn’t muster the energy to go any further.

As I headed towards the beach on the right bank of the “river”, I came across a “detour” sign. Again, not what it seemed to be, unless in this part of the country “detour” means something different, like “warning” or “location” or possibly just “useless information”.

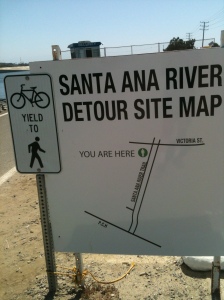

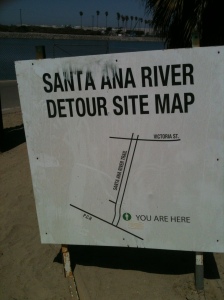

On the East Coast, a detour sign points out an alternative route that takes you from point A to point B when the most direct route is unavailable. Here in Orange County, a “detour” sign simply alerts you to the existence of a detour, not to its actual location. The one I encountered depicted the street behind me (Victoria Street), the street along the beach ahead of me (Pacific Coast Highway, or PCH), and the twin branches of the Santa Ana River Trail connecting the two. (Even the “detour” sign doesn’t acknowledge any actual river in the middle.) Plus there is a “helpful” YOU ARE HERE icon showing the location of the sign itself.

But I knew where I was already. True, I hadn’t known about the detour – so thanks for alerting me, California Map People – but what good is learning about it if I don’t also learn where it is? I figured I had to choose a new route, but all I could do was make my best guess. That turned out to be wrong; what I took to be a side path paralleling the trail on the right bank led straight to construction work blocking both the side path and the trail. I had to walk back to Victoria Street and cross over to the other side of the “river”, where the path was clear all the way to the beach.

At this point you might be thinking what I was thinking: Maybe it’s a cultural thing. Maybe I’m just used to arrows and explicit maps showing actual routes, but in California, marking a map with a big red YOU ARE HERE is the universal symbol for “Don’t walk this way!” Just about then I reached the end of the Trail, where the path on the left bank met the Pacific Coast Highway. And here’s the sign I found there:

“Wait — this side of the river is clear. Why is there a detour sign here? Are they trying to trick people to go to the other bank, where there really is an obstacle? Is this all part of California’s constant campaign to get people to drive instead of walk?”

Of course, this whole incident was harmless, maybe even good for me — providing me with a little extra exercise, a little more familiarity with the neighborhood. The frustration comes from that nebulous announcement from authority: “There is an obstacle ahead . . . maybe. Won’t tell you where it is or how to avoid it, or why or even if you need to worry about it.” Compared to that, ignorance really is bliss. The nebulous announcement from authority generates anxiety without providing any tools for relief.

How often have I counseled people in the grip of that kind of anxiety! Job seekers who were told sternly, “You must have a one-page resume!”, without a sensible explanation of why, how, or under what circumstances, so that professionals with twelve years of relevant experience end up cramming it all onto one quarter-inch-margined page of flat, spare prose in 8-point type. Professionals at all levels who are informed by colleagues or media career gurus, without nuance or elaboration, how critical it is to develop a network on LinkedIn, and who end up spending an hour a day inviting strangers to connect yet spend zero time correcting the spelling errors in their tepid profiles. Students who respond to a professor’s outspoken contempt for conventional essay structure formulas by abandoning not just formula but structure itself. In every case, these people felt trapped between the dual discomforts of having tried to fulfill essentially incomprehensible decrees as best they could while sensing intuitively that their seemingly-required actions were only making them worse off.

The truth is, it is good to sort some things out yourself. It makes you smarter, tougher, more creative. But that doesn’t mean it’s better to start from a place of greater confusion because of the ill-considered declarations of some blowhard “expert”. There are a lot of amazing, dedicated, knowledgeable people out there whom you can rely on for guidance as you make your way through your life’s path. But you will also run into your share of advice-givers — some of them professionals — who, for a variety of reasons (laziness, inexperience, lack of training, rigidity, etc.), will offer advice that really amounts to that nebulous announcement from authority. If somebody tells you there is something you need to worry about in your career planning or job search (or anything, really), but won’t tell you why or how, you need to take that advice with a grain of salt. Go and find out the why and the how yourself, and you’ll have a better sense of how much you really need — or don’t need — to worry.

Very amusing. I was blacklisted for five or seven years – who’s counting? – for minor anti-Vietnam involvement, and wound up re-directed out of my chosen profession. But I did get some medium-term positions out of the experience which wound up enriching my teaching when I finally got back in. Forget “Career Ladder.” Think “Career Lattice.” Or, How to make great lemonade…. Sensible article. Thanks for the funny read on a Friday afternoon. Life is strange, right? – John

It appears that the “detour” signs that the author described and photographed were actually supposed to have markings on them, put there by the construction crew, showing which side of the trail they would be working on for a given day. These types of signs are able to be re-marked frequently, with something like a wax pencil, as the work location changes. Without the critical daily details filled in, the signs are meaningless, like a roadmap without street names or route numbers marked.

A person becomes a true “expert” or “authority” on something precisely because they have done so many times that it becomes second nature to them. Thus, when they try to explain that thing to someone who isn’t an expert, they often skip over details they consider to be so basic as to be “obvious” to them, but may be totally unknown to the inexperienced listener.

I am a professional with almost a decade of experience doing the same kind of work, but I sometimes assume that “any logical person” can do what I do. It’s only when I have to train a new member of my team (as I have had to do recently) that I realize the true extent of my specialized knowledge base.